A few weeks ago I met, as unimaginative as the phrase is, one of my ‘literary heroes’.

He’s an author whose books I’ve dipped into since Down Under joined our family’s selection of toilet entertainment about a decade ago, alongside The Best of Private Eye 1989 and a few Gary Larson cartoons.

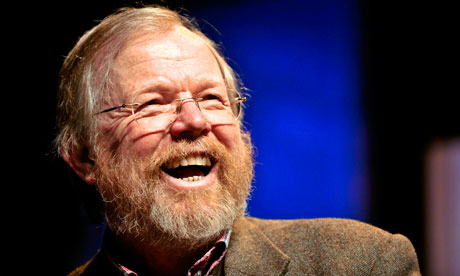

Of course, as a teenager primarily concerned with boys and alcohol, it didn’t occur to me at the time that everybody else knew about Bill Bryson too. To me he was just a hairy man bumbling around Australia, who only really existed every so often in the tiled confines of my parents’ upstairs bathroom. It wasn’t until I grew older and more of his books appeared in the cupboard, that I started to realise just how brilliant a writer this hairy man was. He had, and of course still has, a rare talent that many clever people lack: the ability to make complex (and, it has to be said, potentially dull) information digestible and entertaining. I may have doodled and daydreamed my way through science lessons at school, but when Bill Bryson explained atoms, electrons and quarks in The Short History of Nearly Everything, I was not only gripped, but sometimes laughing out loud. It was a strange feeling then, to find myself sitting at the Dean’s Place Hotel in Alfriston a few weeks ago, looking right at the man I’d spent so much time reading about. Up to that point, he had just been a character from a book. Now here he was, standing right in front of me, actually giving me advice.

“First of all, thank you very much for coming. It’s really very flattering to me and it’s something that always means a lot,” Bill Bryson said, his Iowa twang still noticeable after 40 years of living in Britain. As much as I would like to say he was addressing me personally, I was in fact sitting in an audience of about 80 others, at an hour-long talk organised by the local bookshop Much Ado Books. He was there to promote his latest book, One Summer: America 1927 but, true Bryson-style, he ended up discussing all kinds of things, including his relationship with travelling, writing, England and his family, who we soon discovered were sitting with us in the audience.

| Bryson waiting to begin his talk at Dean's Head Hotel, Alfriston |

“I feel a bit uneasy here for a number of reasons,” Bryson began once the welcoming applause had petered out. “Not least because my two children are here and so if I screw up they’ll never let me forget it. Most places I go, if I do screw up then I can just leave and I don’t see the people ever again. These are people I have to live the rest of my life with.”

Before inviting us to ask our own questions, Bryson spoke about his background in journalism, travel writing, and of course his new book. He first found fame as a travel writer in the late ‘80s, after he published The Lost Continent: Travels in Small-Town America, but, despite his obvious successes, he never intended it to be that way.

“For a first book it attracted quite a lot of attention," he said. "And for that reason my publishers said ‘ok, that’s what you do now, you do travel books.’ But that was not my intention. I enjoyed doing it — I didn’t resist the idea, but after I’d done a dozen or so travel books, there came a point when I decided that I can’t write any more jokes about food I don’t like, or just being confused and muddled. And I was running out of countries to sort of, take the piss out of.”

One of the reasons I’ve always enjoyed Bryson’s books, even as a teenager, is that despite the long and often detailed passages about certain points in history, or things that I’m not particularly interested in (like baseball), the stories themselves are told so well, and they are so pleasantly peppered with funny bits that I just can’t skip over them. In trying to write my own comic passages, I often despair at how easy it seems to come to other writers. How effortlessly they build a story and deliver a punchline by using the right words at the right pace, at just the right tone. Bryson is highly accomplished at doing this, but he was quick to admit to us (much to my delight) that humour doesn’t always flow as well for him as it seems.

“It’s a challenge to write comic passages and it’s an interesting challenge,” he told us. “What’s hard about writing humorously is that when you’re writing you don’t know how the reader is going to respond to it, and you can agonise over punchlines, trying to get the passage exactly right — but you have no idea how it’s going to be received. Still, it’s something I enjoy immensely even though it drives me crazy doing it.”

The ‘agonising’ Bryson mentioned is something most writers know all too well, and not just in terms of comedy. Famous writers, including F Scott Fitzgerald and Sylvia Plath, have spiralled into depression and alcoholism with bouts of writer’s block. The problem with being an avid reader as well as a writer, is that it opens your eyes to all the superb talent out there, and it drives home just how much competition there is to contend with. It’s like a chef doing a tour of all the Michelin starred restaurants in the world and then coming back to his little cafe in a side-alley in Chiswick — is it inspiring to encounter the best, or is it just depressing? I put this thought to Bryson when he opened the floor to questions (after a fair amount of frantic arm waving - mine, not his).

“Somebody gave me a great deal of comfort when I was an aspiring writer myself,” he told me, while I tried to process the incredible fact that I was talking to Bill Bryson. “Go into any bookshop and look at all of the titles. Hundreds and hundreds of titles. Thousands of titles. They’re all written by people who first of all nobody had heard of. And then just look at the books. I don’t know how good a writer you are or not, but I can tell you that you’re a lot better than a lot of people who get published. There’s a lot of bad writing out there. You cannot be so bad that you would be as bad as Jeffrey Archer. There’s room for all of us. Publishing is an amazingly vast and sprawling thing. So don’t give up, and don’t worry that people won’t read you because one day they very well may.”

Before he moved on there was something else I wanted to know. While reading his travel books, I’d always wondered how the writing process itself changed the way he viewed or enjoyed a place. I imagined he would always have to be taking notes at every museum he found, every local he spoke to. On the few occasions that I have travelled alone, I’ve spent a great deal of that time writing — in cafes, in restaurants, on train journeys. For me it’s an enjoyable experience that helps to consolidate my thoughts. For Bryson, however, writing is more of a burden. “What I really enjoy, just for pleasure,” he said, “Is going with my wife and kids and not having the burden of having to write about it – not having to take notes or think about it. Travelling to gather material is not all that fun. Travelling with my wife and kids is.”

Previously in the talk, he’d told us that he conducts his research alone. This, he said, is “the most fun part of the book”. The writing itself is “just hard and it’s not fun. It’s just a job I have to get through.” He mentioned this lack of enjoyment again in answer to my question: “When I’m writing, I need to be doing it on my own. It’s not an experience that I can enjoyably share with my wife and kids or anything like that. There have been times that they’ve come along with me that aren’t necessarily recorded in the book. But by and large it has to be a selfish experience.” When he goes out for a walk, he needs to be free to make his own decisions — whether to go left at a T-junction, or right. He compared travelling around with others to being in a “cocoon, a little bubble that becomes your culture, your personal life that you’re just moving around a different place with”.

At the signing after the talk, Bryson graciously shook hands with and spoke to just about every audience member there. It was clear to see he wasn’t just there to sell books: he was there because now, after months of researching and writing in isolation, he could finally come to meet the people who enjoy his work. When it was my turn, he thanked me for my question and asked a little about my writing. He told me again not to worry, just to persevere because, despite his OBE, his awards, his honourary degrees and his global success, he still knows exactly how it feels to want to throw your laptop out of the window, lock yourself in a cupboard and never write another word.

It’s a burden a lot of writers carry, but we have to carry it with pride, if only for the small chance that one day, somebody might want to read what we have written.